Moore County, North Carolina has one of the largest populations of Highland Scottish descendants in the U.S.A. About 150,000 Scottish people emigrated to America between 1600 and 1776,1 and North Carolina had the largest number of Highland settlers in America. Between 1739 and 1776 about 50,000 Highlanders came to the the Cape Fear River Valley in what is now the state of North Carolina for relief from economic and political repression.2 Remnants of the Highland culture survive in local names, liberally sprinkled with Mc’s, the prefix which meant “son of” in Gaelic, in numerous Presbyterian churches, and place names like Caledonia, Aberdeen, and Cameron.The McDonald Family Cemetery on Crains Creek near Cameron contains up to ninety graves of Scottish immigrants and their descendants. The oldest marked grave is dated 1796, and at least one stone was engraved to record that the deceased, John Ferguson, was “born in Scotland.” The stone of Sally McDonald, wife of Angus, reveals that she was a native of the Isle of Skye. Some bear Masonic symbols.3 A deed to the cemetery was recorded in 1911, by A.B. McDonald, Donald McDonald, and J.D. Richardson.

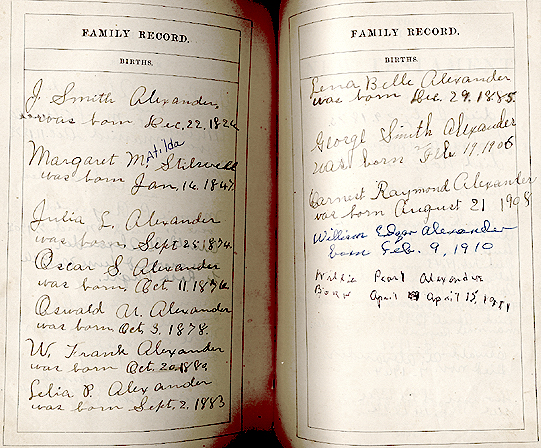

Several members and relatives of the Richardson family are buried on Crains Creek. Hattie Belle Richardson was born August 13, 1896 in Moore County, to Mr. and Mrs. John Dolphus Richardson. She died September 26, 1898. She is buried beside her maternal grandfather, John Finlayson McDonald, born July 31, 1817 in Cumberland County, N.C., to Angus McDonald and Mary Finlayson. His first wife was Sarah Strickland, who died in 1852. The couple belonged to Cypress Presbyterian Church in Harnett County. They had sons named Angus and Malcom Daniel.

John F. McDonald and his second wife, Jennet Isabella Patterson belonged to Union Presbyterian Church, located between Carthage and Vass. The couple farmed near Crains Creek, where he also was a millwright. He died in Moore County on February 20, 1899. Jennet was born about 1843, also in Cumberland County, to Neill Patterson (1808-1877) and Margaret Ann Eliza McLean (1817-1891). She died August 20, 1901,4 and is probably the occupant of the unmarked grave on the other side of her husband.

To the right of the graves of John Finlayson and Jennet Patterson McDonald is the grave of their daughter, Margaret Ann McDonald Hicks, who was born September 8, 1872 in Moore County. Three of her children are buried next to her. Twins Margaret May and Mack McDonald Hicks were born April 10, 1904. Their mother died shortly after their birth on May 13, 1904. Margaret May died June 16, 1904, and Mack died June 22, 1904.

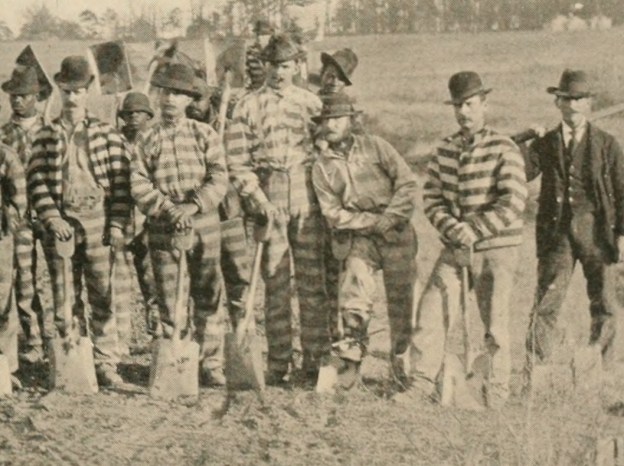

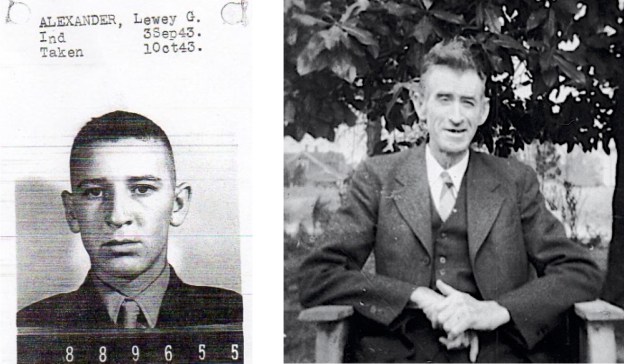

The twins’ brother, Neil Abner Curtis Hicks, was born February 28, 1893 and served in the 3rd Provisional Regiment, 156th Depot Brigade in World War I. He died at Camp Sevier Base Hospital in South Carolina on October 4, 1918. The large monument in the photograph at the top of the page marks his grave, the last burial in the cemetery. In 1918, thousands of soldiers were treated for influenza at Camp Sevier and hundreds died, victims of the Spanish flu epidemic.5

Margaret McDonald Hicks’ husband was Abner Fields Hicks, who remarried after the death of his wife and is buried at Johnson Grove in Vass.6

John Finlayson and Jennet Patterson McDonald were also the parents of Neill Archibald McDonald, born July 24,1869 in Moore County. He married Marie Gottschalk of Louisiana, and they had thirteen children. He was a textile worker in High Point, N.C., and died there on January 26, 1969.7

Another daughter of John and Jennet McDonald was Mary Arabella, born in 1867, wife of J.D. Richardson and mother of Hattie Belle, as above.

Other family groups in the McDonald-Ferguson Cemetery:

Murdoch and Mary McDonald Ferguson

John and Maria Ferguson

Children of Daniel McDonald

D. McDonald

John and Nancy McDonald

Angus McDonald

Other individuals:

Nancy McDonald

Norman McDonald (1736-1796) oldest inscription

John Cammeron

Theodota McDonald

Catherine McDonald

Dougal McDonald

John Monk

Elizabeth Currie, wife of John M. Currie

Catherine Arnold, wife of Henry Arnold

Daniel McDonald

Catherine McDonald, wife of Donald McDonald

Daniel McDougald

Sergeant Finley McDonald (N.C. Regt. Cont. Line) (DAR memorial, not a grave)8

Footnotes:

- David Dodson, The Original Scots Colonists of Early America: 1612-1783, (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1989), page v.

- Douglas F. Kelly, Carolina Scots: An Historical and Genealogical Study of Over 100 Years of Emigration. (Dillon SC: 1739 Publications, 1998) pp. 79, 81, 209-211.

- Gravestones in the McDonald family cemetery on Crains Creek in Cameron, N. C., visited in 2003.

- Alex M. Patterson, Highland Scots Pattersons of North Carolina and Related Families. (Raleigh: Contemporary Lithographers, Inc., 1979), pp. 159-194; James Vann Comer, Gone and Almost Forgotten: Crain’s Creek Community, (Sanford: James Vann Comer, 1986), p. 104.

- Office of Medical History: Office of the Surgeon General, “Extracts from Reports Relative to Influenza, Pneumonia, and Respiratory Diseases,” April 4, 2003, accessed online July 1, 2006.

- Patterson, cited above, pp. 186-192; Interviews with Willie Alexander Carr by the author, April 1, 2002; Curtis Hicks, WWI draft registration card, no. 32, Carthage NC, June 5, 1918; Mary MacDonald Richardson, Death Certificates, Vol. 1801, (Raleigh: North Carolina State Archives) p. 308.

- Patterson, cited above, p. 182; Population Schedule of the Ninth Census of the United States: 1870, Roll 1149, North Carolina, Moore County, Greenwood District, (Washington: National Archives and Record Service, 1965) p. 533.

- Kelly, cited above; Rassie E. Wicker, Miscellaneous Ancient Records of Moore County, North Carolina, (Southern Pines: The Moore County Historical Association, 1971); Anthony E. Parker, compiler, A Guide to Moore County Cemeteries, (Southern Pines: The Moore County Historical Association, 1975).

Copyright 2001 by Glenda Alexander, updated Oct. 2023; Standard copyright restrictions apply.