Clady F. Johnson was born in 1902 in Stokes County, N. C., the eighth child of Lindsay Johnson and Martha White.

The following article about Clady appeared in the Western Sentinel newspaper in April of 1921:

“Clady Johnson Sent to Roads for Month:

“Can’t you get a job? asked Judge Hartman of a young white man in the city court this morning, who was on trial for being a vagrant. ‘I can,’ was the reply, ‘but they won’t pay over $1.50 a day, and before I’ll work for that, I’ll go to the county roads.’

“‘Thirty days,’ said the judge.

“‘I understand you are a rather hard sort of a fellow,’ said the judge, and the young man replied:

“‘I am one of these fellows that loves a fight when I get started. No, sirree, I won’t take anything off of anybody.’

“The young man’s replies to the court were rather abrupt.

“The defendant’s name was Clady Johnson, and he was arrested last night and held in jail until this morning.”

Clady’s Story—Low Wages

When Clady was about 17 years old, his parents moved from a farm in Stokes County, N. C., to Winston-Salem. There he, his brother Jim, and their father worked at R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. Clady was able to read and write, and he had a third-grade education.

While living in Winston-Salem, Clady apparently quit his job in the cigarette factory, unhappy with the low wages. In the 1920’s, a young man with no occupation could easily be accused of being a vagrant, by loitering in public places, possibly drinking (in the time of Prohibition) or fighting.

$1.50 for a day’s work (in 1921 usually nine hours) averages out to 16 cents per hour. Sixteen cents back then had the buying power of $2.85 in 2025, so far from a living wage that no wonder Clady refused to accept it.

In the labor market then, race and gender affected wages, just as they do now, but with more extremes. In the tobacco industry in Virginia in 1928, the highest wage was paid to white men, at 53 cents/hour. The wage dropped to 31 cents for white women, 29 cents for black men, and 16 cents for black women.

Black women were the largest group employed by R. J. Reynolds, and perhaps this affected the rate of pay, even for white men, who could easily be replaced by much cheaper labor.

In the many textile factories in the area, things were no better. The average hourly earnings for a male in the cotton textile industry in North Carolina in 1920 was about 50 cents. In 1922, it actually fell, to 30 cents. There was a major economic recession in 1921 and many newspaper articles report cuts in industrial wages. Fifty cents was still more than Clady claimed to be paid at RJR. In fact, he was earning less than half the national average for a factory worker in the U. S. in 1921.

Working on the Chain Gang

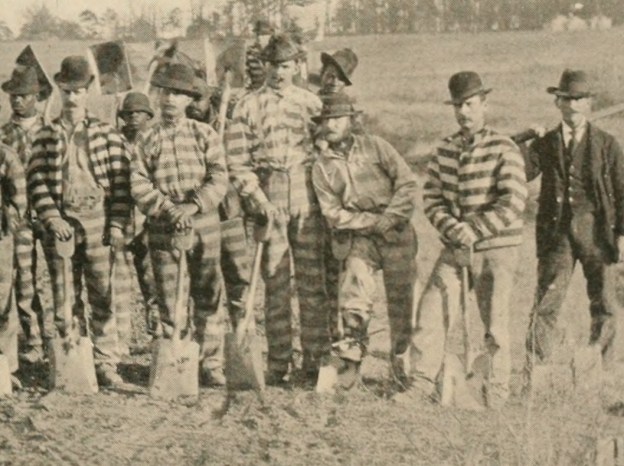

Clady’s bravado in telling the judge he’d rather work on the roads may have been reduced quite a bit by the reality of working on a chain gang. Chain gangs were the low-cost solution to road building and maintenance until the 1950’s. Just like in the movies, the men were dressed in black and white striped uniforms and had iron shackles on their ankles joined by a chain short enough to prevent them from running. They were housed in temporary camps located near their work site, in all weathers, guarded by men with shotguns, and flogged for misbehavior. They worked with picks and shovels, doing hard labor that is now done by machines.

Clady’s change in attitude was revealed when his name appeared in the newspaper again, this time in a list of thirty-three white men who had escaped the chain gang over a ten-year period.

Life Afterward

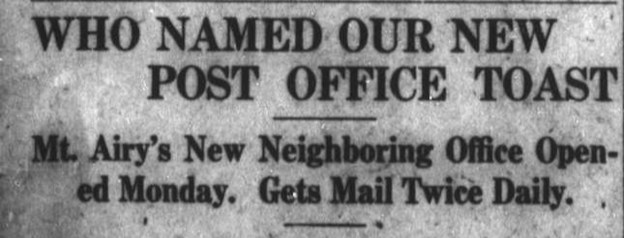

The family moved to Mt. Airy soon afterward. In 1930, Lindsay Johnson was no longer working and his three youngest sons were all working in a furniture factory, Clady, as a sprayer. Lindsay died in 1931 at age 70 and Martha died in 1933.

By the 1940 census, Clady was living with his youngest sister, Mary, in Washington, D. C. He was unemployed and unable to work. His brothers Elijah and John, also living in Mary’s household, both registered for the WWII draft. Clady apparently never registered, perhaps because of his health, and he died in 1941 of respiratory illnesses.

Sources:

The Western Sentinel (Winston-Salem, N.C.) Apr 23, 1921, p. 17. “Clady Johnson Sent to Roads for Month.”

“Winston-Salem Journal, Dec. 15, 1922, p. 4. “Reward Offered for Runaways,”

Journal Article, “Wage Rates and Hours of Labor in North Carolina Industry,” H. M. Douty; Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Oct., 1936), pp. 175-188.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: FRASER Newsletter, July 1930, Volume 31, Number 1, Date: July 1930. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/monthly-labor-review-6130/july-1930-608191?page=176

https://www.myamortizationchart.com/inflation-calculator/], accessed 10 July 2025.

U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics/Data Tools/Charts and Applications/Inflation Calculator; https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm, accessed 4 June 2025.

Handbook of labor statistics / U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics 1936, Accessed online on 4 June 2025, at https://babel.hathitrust.org/

1910 U.S. Census, Quaker Gap, Stokes County, N. C.; NARA Microfilm # T624-1128; Enumeration District 182, p. 2B.

1920 U.S. Census, Winston Township, Forsyth County, N. C.; E. D. 90, pp. 8A-8B.

Winston-Salem, N. C., City Directory, 1921, p. 279; Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989, database on-line.

Ernest H. Miller, Miller’s Mount Airy, N. C. City Directory, Asheville NC: Southern Directory Co., 1928-1929, pp. 170-171.

1930 U.S. Census, Mt. Airy township, 2nd Ward, Surry County, N. C., ED 86-12, “Lindsay J. Johnson” family, p. 3B.

1940 U. S. Census, Washington, D. C., Block 15, E. D. 27B, p. 61B; April 9, 1940; accessed on ancestry.com.

Certificate of Death of Clady Johnson, March 7, 1941, District of Columbia, Health Dept., Bureau of Vital Statistics.

Jesse Allen Johnson, (1838-1920) was the son of Henderson Johnson and Amelia Norman. He was born in the Westfield District of Surry County, N. C., where he lived for several decades. His grandfather, Wright Johnson, was a well-known “local preacher” and deacon of the early Methodist denomination.

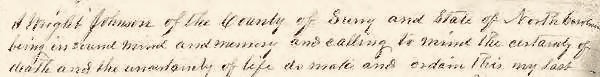

Jesse Allen Johnson, (1838-1920) was the son of Henderson Johnson and Amelia Norman. He was born in the Westfield District of Surry County, N. C., where he lived for several decades. His grandfather, Wright Johnson, was a well-known “local preacher” and deacon of the early Methodist denomination.