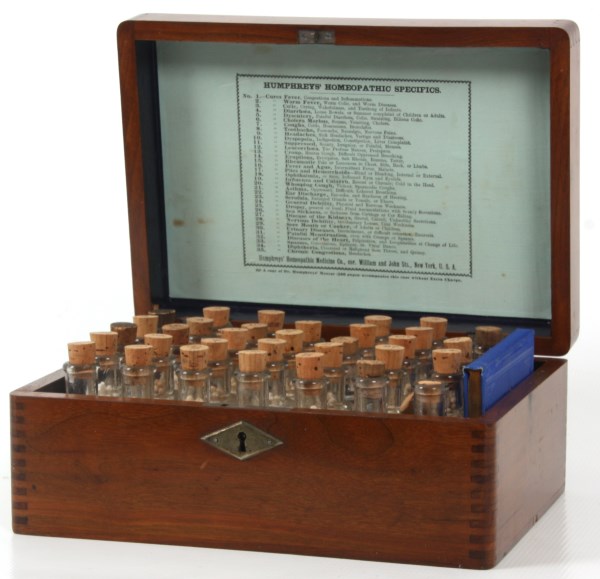

An ad for homeopathic medicines in The Charlotte Observer in 1876 had an extensive list of illnesses and health problems of the time. Homeopathic medications are extremely diluted plant, mineral, or animal extracts used to treat disease. The object is to produce an immune response in the body by using a very low dose of a substance that will provoke the symptoms of the illness. In 1876, homeopathic medicine had been around in Europe for nearly a hundred years. It is still used, but in the U. S. A., it has never been approved by the FDA.

“The Mild Power CURES

Humphreys’ Homeopathic Specifics:

Been in general use for twenty years.”

List of Conditions to be cured:

“1. Fevers, Congestion, and Inflammation

2. Worms, Worm Fever, Worm Colic

3. Crying Colic, or teething of Infants

4. Diarrhea of Children or adults

5. Dysentery, Griping, Bilious Colic

6. Cholera-Morbus, Vomiting

7. Coughs, Colds, Bronchitis

8. Neuralgia, Toothache, Faceache

9. Headaches, Sick Headaches, Vertigo

10. Dyspepsia, Bilious Stomach

11. Suppressed or Painful Periods

12. White, too Profuse Periods

13. Croup, Cough, Difficult Breathing

14. Salt Rheum, Erysipelas, Eruptions

15. Rheumatism, Rheumatic Pains

16. Fever and Ague, Chill Fever, Agues

17. Piles, blind or bleeding

18. Ophthalmy, and Sore or Weak Eyes

19. Catarrh, scute or chronic, Influenza

20. Whooping-Cough, violent coughs

21. Asthma, oppressed Breathing

22. Ear Discharges, impaired Hearing

23. Scrofula, enlarged glands, Swellings

24. General Debility, Physical Weakness

25. Dropsy and scanty Secretions

26. Sea-sickness, sickness from riding

27. Kidney Disease, Gravel

28. Nervous Debility, seminal weakness or involuntary discharges

29. Sore Mouth, canker

30. Urinary Weakness, wetting the bed

31. Painful Periods, with Spasms

32. Disease of Heart, palpitations, etc.

33. Epilepsy, Spasms, St. Vitus’ Dance

34. Diphtheria, ulcerated sore throat

35. Chronic Congestions and Eruptions”

Each category was treated by a separate homeopathic remedy, which could be bought singly, in small bottles, or in a leather case containing all thirty-five of them. plus a manual, sold by “all druggists” in Charlotte. This product was distributed from No. 562 Broadway, N. Y.

Source: Ad in The Charlotte Observer, 18 Aug. 1876, p. 4; accessed online through newspapers.com.

Glossary:

2. Worms: Different kinds of parasites in the digestive system or under the skin. Roundworms, including pinworms and ascariasis can cause fever.

3. Colic: The symptom of colic is unexplained crying in babies, usually with behavior that shows they are in pain. Doctors seem to think the most likely causes are teething and digestive pain, but none of them seem to really know.

5. Dysentery is bloody diarrhea, caused by bacteria. Griping is intestinal pain. Bilious colic is pain caused by gallstones blocking the bile ducts.

6. Cholera morbus is an old term for cholera, a gastrointestinal infection caused by bacteria, with the major symptom being large amounts of watery diarrhea lasting for days. There were six cholera pandemics during the 1800’s. Caused by contaminated water, better sanitation helped to bring it under control.

8. Neuralgia is a sharp, burning pain along the path of a nerve. caused by damage to the nerve. it can affect any part of the body.

9. Sick headache is accompanied by nausea and includes migraines.

10. Dyspepsia includes different kinds of indigestion. Bilious stomach was apparently what we now call acid reflux.

12. White period is a white discharge before the normal menstrual period, caused by hormonal changes. It can be normal, or be a symptom of disease or of pregnancy.

13. Croup is an infection and swelling of the upper airway, which makes it hard to breathe, and it causes a cough that sounds like barking.

14. Salt rheum was another name for eczema. Erysipelas is a bacterial skin infection that causes a firy red rash. An eruption was a rash.

15. Rheumatism is inflammation in muscles, now usually called rheumatoid arthritis. It causes chronic pain and soreness.

16. Ague was malaria or some other illness causing fever and shivering.

17. Piles are hemorrhoids.

18. Ophthalmy was inflammation of the eyes.

19. Catarrh is excessive mucus in the nose or throat, now usually called postnasal drip.

20. Whooping cough is a very contagious respiratory infection that causes severe coughing.

23. Scrofula is an infection in the lymph nodes of the neck by the same bacteria as tuberculosis.

25. Dropsy is edema, or fluid retention in body tissues.

27. Gravel is kidney stones.

33. St. Vitus’ Dance is an auto-immune disease which can be a side effect of rheumatic fever. It causes uncontrolable jerking movements in the the face, hands and feet.

34. Diphtheria is a bacterial infection that causes fever and severe sore throat. It used to cause the death of many children. Most people in the U. S. Are now vaccinated against diphtheria and whooping cough.

[Defined with help from Mayo Clinic, NIH, and Wikipedia, among others.]