September 25th, this week, was “World Lung Day.”The World Health Organization, concerned about a world-wide epidemic of tuberculosis, got a hearing this week at the United Nations to ask for funding to fight the leading infectious killer of human beings in the world today.

The United States gained control over the disease during the mid-20th century, after the introduction of antibiotics and x-rays. I remember the mobile x-ray unit that used to visit the county seat at least once a year. My mother and other people with family members who had the disease were required to get a yearly x-ray so that the illness could be promptly diagnosed and treated. My brothers and I would wait in the car on the courthouse square while she stood in line.

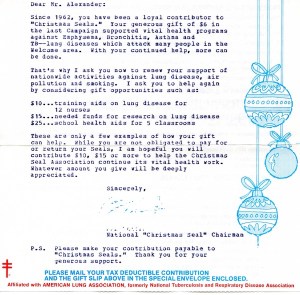

Apparently this was a common experience all across the U. S. The American Lung Association raised money from the sale of Christmas and Easter Seals, stamp-like stickers you could put on your cards and letters, advertising the organization’s efforts against “lung diseases, air pollution and smoking.”

My mother’s half-sister, Reba Oakley, and Reba’s mother and grandfather, from Surry County, N. C., all died of tuberculosis. In 1912, when Reba was born, T. B. was causing more deaths than heart disease or cancer, and The American Lung Association was less than a decade old. Reba’s mother died of the disease only 3 years later.

Reba’s grandfather, William Tyson Snow, had already died in 1906, of “consumption,” as it was called then. The family apparently believed that the infection was latent in Reba’s lungs for decades. She became ill as an adult and was treated at a state sanitarium for several years, before succumbing to the debilitating effects of T. B. at age 34.

A latent infection from T. B. is now said to be very rare. It is possible that Reba was infected as an adult. However, because of her infection, her family were all required to be x-rayed yearly for several years. Fortunately, they all remained healthy.

Poverty contributes to the prevalence of the disease in Africa and Asia today. However, it’s easy to forget that only a century ago, many of our own citizens were working on subsistence farms and spending long days in textile and other factories, where their exposure to lint and other air pollutants made them sick. As unemployment and homelessness grow in our population, so do diseases we often consider misfortunes of the past.

Copyright 2018 by Glenda Alexander. All Rights Reserved.

More about Reba Oakley and family:

http://home.earthlink.net/~glendaalex/reba.htm

Sources consulted online:

Esther Johnson of the Surry County Genealogical Association commented, concerning the Mt. Airy Granite Quarry: “That was one of the things that happened to people who worked in our Quarry here in Mt. Airy. Everyone at school had to take a test for TB.”

North Carolina has 27 Historic Sites that offer hands-on history programs. Yesterday I went to the House in the Horseshoe, near Sanford, for a workshop on 18th century clothing. Gail Mortensen-Frazer showed us outfits she sewed, in the authentic manner of the time, stitch by tiny stitch, from fabrics the American colonists could weave, like linen and wool, and fabrics only the wealthy could buy, like cotton and silk. She wore an authentic outfit for a housewife of the Revolutionary period, with layers of shift, petticoats, corset, bodice, scarf, and apron, and no less than three cotton caps, as well as hand-knit stockings and cobbled shoes.

North Carolina has 27 Historic Sites that offer hands-on history programs. Yesterday I went to the House in the Horseshoe, near Sanford, for a workshop on 18th century clothing. Gail Mortensen-Frazer showed us outfits she sewed, in the authentic manner of the time, stitch by tiny stitch, from fabrics the American colonists could weave, like linen and wool, and fabrics only the wealthy could buy, like cotton and silk. She wore an authentic outfit for a housewife of the Revolutionary period, with layers of shift, petticoats, corset, bodice, scarf, and apron, and no less than three cotton caps, as well as hand-knit stockings and cobbled shoes.

I knew my grandmother was important. She was a modest little lady, even considering that she could put anybody in the family in their place with a sharp remark or a stern look. She never had her hair cut or wore a skirt any higher than mid-calf. She ignored the doctor’s advice to take a walk every day because she thought it unladylike to go walking down a public street like that. She preferred to stay out of the sun and do needlework, read her Bible, and watch the soaps and country music shows.

I knew my grandmother was important. She was a modest little lady, even considering that she could put anybody in the family in their place with a sharp remark or a stern look. She never had her hair cut or wore a skirt any higher than mid-calf. She ignored the doctor’s advice to take a walk every day because she thought it unladylike to go walking down a public street like that. She preferred to stay out of the sun and do needlework, read her Bible, and watch the soaps and country music shows. I posted a message on the board to thank them and let them know that I had found Elijah with a “J.” No one lol-ed or even tehe-ed, and I know, being genealogists, they are at least as old as I am, and they should get the reference. I will excuse them, however, as most of them have unsubscribed and moved over to the Facebook page. Message boards are apparently becoming history, too.

I posted a message on the board to thank them and let them know that I had found Elijah with a “J.” No one lol-ed or even tehe-ed, and I know, being genealogists, they are at least as old as I am, and they should get the reference. I will excuse them, however, as most of them have unsubscribed and moved over to the Facebook page. Message boards are apparently becoming history, too.

This is a quilt honoring my four great-grandmothers.

This is a quilt honoring my four great-grandmothers. Moore County, North Carolina has one of the largest populations of Highland Scottish descendants in the U.S.A. About 150,000 Scottish people emigrated to America between 1600 and 1776, and North Carolina had the largest number of Highland settlers in America. Between 1739 and 1776 about 50,000 Highlanders came to the the Cape Fear River Valley for relief from economic and political repression. Remnants of the Highland culture survive in local names, liberally sprinkled with Mc’s, the suffix which meant “son of” in Gaelic, in numerous Presbyterian churches, and place names like Caledonia, Cameron, and Aberdeen.

Moore County, North Carolina has one of the largest populations of Highland Scottish descendants in the U.S.A. About 150,000 Scottish people emigrated to America between 1600 and 1776, and North Carolina had the largest number of Highland settlers in America. Between 1739 and 1776 about 50,000 Highlanders came to the the Cape Fear River Valley for relief from economic and political repression. Remnants of the Highland culture survive in local names, liberally sprinkled with Mc’s, the suffix which meant “son of” in Gaelic, in numerous Presbyterian churches, and place names like Caledonia, Cameron, and Aberdeen. Last week, I was in Aberdeen, driving along Bethesda Road, also called N. C. Highway 5.

Last week, I was in Aberdeen, driving along Bethesda Road, also called N. C. Highway 5. Because of the frequent naming of offspring for their parents and grandparents, the many Duncans, Malcolms, Anguses, Daniels, and Archibalds, as well as Marys, Margarets, Floras and Jennets have made the McDonalds and Pattersons two of my greatest challenges in searching out the family history. Read the stones in the cemetery, and you will see.

Because of the frequent naming of offspring for their parents and grandparents, the many Duncans, Malcolms, Anguses, Daniels, and Archibalds, as well as Marys, Margarets, Floras and Jennets have made the McDonalds and Pattersons two of my greatest challenges in searching out the family history. Read the stones in the cemetery, and you will see.