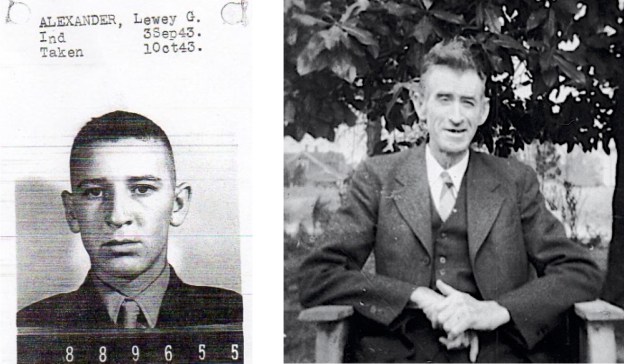

The first Confederate Army conscription in April of 1862 called up men ages 18-35. Smith and his identical twin, Silas Washington Alexander were age 36. While Smith remained in the local militia, “Wash” and their two youngest brothers enlisted in Company B, 13th N. C. Infantry Regiment.

Oswald and Ulysses Columbus Alexander, as well as some of their cousins, served as musicians in the company. The custom was for a band of mostly brass instruments and drums to play during battle, to encourage the troops. The Alexanders lived in Mecklenburg County, in the Sharon church community, which had a band that performed for special occasions. The brothers were, most likely, members of that band.

Washington Alexander was elected to be a Second Lieutenant for Company B. His company fought in a long list of battles, and Washington was wounded at Williamsburg in May of 1862. Later that year, when the company was reduced by the high number of casualties, Wash would find himself the leading officer of the company.

The second conscription later in 1862 called on older men to serve. Smith left the Home Guard in March 1863, for Company F of the 5th Regiment of North Carolina Cavalry, also called the 63rd Regiment of N. C. Troops. His brothers James Wallace, age 38, and William Newton, 35, enlisted in the same company, and they served together on horseback.

Gettysburg

Company F served in battles that included the famous Battle of Gettysburg on July 1-3, 1863, as part of the Army of Northern Virginia, under General Robert E. Lee. The cavalry’s duty during the battle was mainly in security and communications.

At Gettysburg, the Confederates, numbering about 75,000, fought against the Army of the Potomac, about 85,000 soldiers. It was a decisive and bloody battle in which the Confederates were turned back and retreated toward the flooded Potomac River. Company F, as part of Robertson’s Brigade, protected the flanks of the army as they crossed the river. Confederate casualties were huge, with almost 4,000 killed and well over 18.000 wounded. Union casualties were of similar numbers.

About one month later, on August 3, 1863, James Wallace Alexander died in Charlottesville, Virginia of typhoid fever. As many as 80% of soldiers’ deaths during the war were from sickness rather than wounds, as they lived outdoors in all weathers, used water from streams they themselves contaminated, and were constantly exposed to contagious diseases.

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire

Smith’s name was listed on a hospital register in Richmond in September of 1863, apparently with a gunshot wound. William was wounded in June 1864, hospitalized in Charlotte with typhoid the following November, and returned to duty in January 1865.

Washington resigned his commission as an officer in September of 1862, citing the fact that he was left as the leading officer of Company B, and that he was too ill to fulfill his duties. Columbus was taken prisoner in the final battle of the war at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, and he later died of disease as a prisoner of war. Oswald survived the war and returned home, along with Smith and William. They had lost two brothers, several cousins and friends and suffered injuries that would affect them the rest of their lives.

On a lighter note:

Cousin Ham the Bad A**: “Get this horse off me or I’ll shoot you.”

Decades after the war, an old soldier named Paul B. Means, a former Colonel in Company F, wrote a story about a private in his company called “Ham,” (Hamilton) Alexander. Ham and his brother, Sydenham, were cousins a few times removed from Smith and his brothers. Ham was involved in heavy action during the Bristoe Campaign, around October 11, 1863. He turned his horse around too quickly and the horse fell, trapping him underneath. The resourceful Ham aimed his rifle at a dismounted Yankee, took him prisoner, and then made his prisoner get the horse off him.7

True story? You decide.

Sources:

1. Confederate Muster Rolls in the files of the N. C. State Dept. of Archives and History, Raleigh, N. C.

2. Stephen E. Bradley, North Carolina Confederate Militia Officers Roster: As Contained in the Adjunct General’s Officers Roster, (Wilmington, N. C.: Broadfoot Publishing Co., 1992), p. 233; Bradley, North Carolina Confederate Home Guard Examinations 1863-1864, (Keysville, Va.: the author, 1993) pp i, ii.

3. Louis H. Manarin, North Carolina Troops: 1861-1865 A Roster, Vol. 2–Cavalry, (Raleigh: N. C. State Dept. of Archives and History, 1968), pp. 367-414.; Janet B. Hewett, The Roster of Confederate Soldiers 1861-1865, Vol. I (Wilmington, NC, 1995), p. 92.; Confederate Muster Rolls in the files of the N. C. State Dept of Archives and History, Raleigh, N. C.

4. “Gettysburg,” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gettysburg, The American Battlefield Trust, accessed 5 Aug. 2025.

5. Walter Clark, editor, Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-65, 5 volumes, (Goldsboro, N. C.: published by the State of North Carolina, 1901,) p.577.

© 2025 by Glenda Alexander. Standard copyright restrictions apply.